Location and prehistory

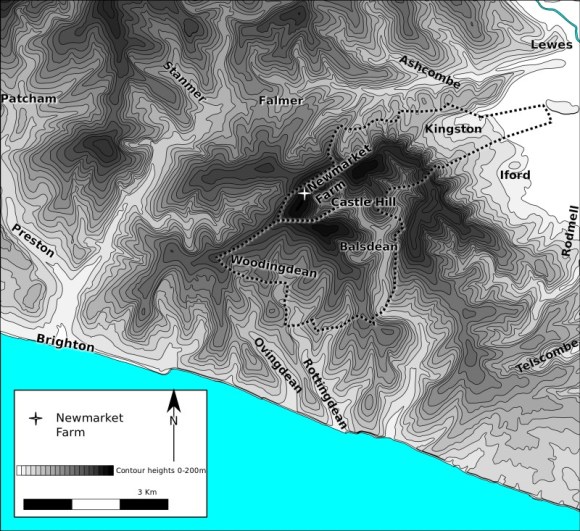

Newmarket Hill is the highest hill of a connecting number of ridges encircling the many valley bottom settlements and farms east of Brighton; Bevendean, Moulescombe, Falmer, Ashcombe (south), Southover (near Lewes), the villages of the lower Ouse Valley, Balsdean, Rottingdean, Ovingdean, Roedean, and Whitehawk. In prehistoric times such ridges were used as trackways. Newmarket Hill, at the centre of this web of ridges and valleys between Brighton and Lewes, would have seen much traffic over the ages.

As a teenager, I (David) found a broken ceremonial polished axehead dating from Neolithic times in a ploughed field on Newmarket Hill. These first farmers built a causewayed enclosure on nearby Whitehawk Hill above Brighton. Just like the polished axehead, it too was probably used for ceremonial purposes. The thin, but fertile, chalk soils were some of the earliest to be cleared of their woodland cover for crops and livestock. At the bottom of the Whitehawk causewayed enclosure’s ditches, archaeologists found the long dead remains of snail shells that today would be expected to be found in woodland clearings; evidence that it remained cleared for the duration of its existence. This appears to be exceptional, for elsewhere on the downs the evidence is that such clearings were normally both small and temporary in an otherwise forested landscape. The population of the whole of the Britain at this time has been estimated to have just been tens of thousands, and may have lived in temporary clearings created in the process of slash and burn agriculture.(1)

There is evidence of trading during this period, so the track between Brighton and Lewes known as Juggs Road, running over Newmarket Hill, was almost certainly in use at this time.

Romans

As Britain’s population increased, more and more of the downland was cleared of its trees for grazing, and put to the plough for cereals. By Roman times the whole of this downland area was almost certainly being heavily farmed. It is supposed that these Downs were most likely more densely inhabited by about A.D. 100 than at any other period since, and that it was at least as put under the plough as it is today.(2) There is evidence that, though not a military road, the track between Brighton and Lewes, known as Juggs Road, was used as a major east-west route between Lewes, Brighton, and thence to Chichester at the foot of the Downs along the northern edge of the coastal plain. It is likely that the route was an ancient one, even by Roman times. A small hoard of Roman coins was found next to the Juggs Road, near the top of Newmarket Hill. Such hoards were often buried by the side of roads.(3)

Saxons

With the collapse of the Roman Empire came a collapse in infrastructure, population, and thus a large decline in the downland farming. It is likely that scrub and woodland would have returned to cover much of the Downland hills and valleys. The Saxons were slow to establish themselves, though clues to their legacy are to be found in the burial mounds on nearby Castle Hill, The Bostle as well as the place-names of their many farms and settlements in the area. The nearby settlements of Falmer to the north, Kingston to the east, and Balsdean to the south, all show evidence of being Saxon in origin. However, it was Kingston that, at least by Norman times, seems to have held the ridge, hill top, and southern slopes of Newmarket Hill. Kingston, before the Norman conquest, was one of many landholdings of Saxon royalty. It was an agriculturally rich parish.

The return of trees to our Downs, for example, was also not necessarily a return to a savage untamed wilderness. Our intensively farmed Romano-British arable fields were expensive to manage. Over a thousand years later, at the start of the Second World War, this was the experience of Balsdean farmer, Guy Woodman. He was forced to obtain two expensive tractors to plough his new arable fields. But Dalgety — who took on the Balsdean Farm tenancy from him after the war — returned the farm to a much less intensive ranch style, which it had been before the war. It was cheaper and easier to run; the lower outputs were offset by considerably lower costs.

As can be seen today, the chalk grassland naturally wants to return to a much more forested landscape. For the late/post-Roman Balsdean Downs, imagine a landscape like that of the New Forest. There are two possibilities; either a parkland type of environment, with lots of grazing among isolated trees (similar to Bronze Age times), or a more dense, generally closed canopy woodland with patchworks of clearings (Neolithic).

Early Medieval Downs

The earliest discovered and excavated, culturally Saxon, post-Roman, settlements on the Downs were on ridge-tops. Later in the mid-Saxon, early Medieval period (8th century), these settlements moved down into valley bottoms, eventually becoming the villages which survive today. Bishopstone (near Newhaven) was one of them. From such limited information it was initially presumed that the earliest Saxon conquerors, nervous of attacks from local Britons, congregated on the hilltops. The more sheltered valley bottoms were only occupied some two or three hundred years later, once the native Britons had been driven out of the area.

Now that modern sophisticated DNA testing, isotopic analysis, and better dating techniques have become available to archaeologists the story has been revised. Also, a significant number of early post-Roman (culturally Saxon) valley bottom sites have been discovered. Simply speaking, hilltop sites are easier to find, and the peoples who were all considered to be Saxon invaders have turned out to be almost all native British who had adopted a largely Saxon way of life. Then, during what some now call the early Medieval period (for our purposes, the 8th to 10th centuries), many of our villages and farm settlements moved to the more sheltered and fertile valley bottoms.

Most of our local ancient South Down farms and villages, from placename evidence, were established or continued their existence in this period:

- Balsdean — Beald’s valley;

- Bevendean — Valley of Beofa’s people;

- Falmer — Fallow mere, dark pool;

- Kingston — King’s farm/settlement;

- Ovingdean — Valley of Ufa’s or Ofa’s people;

- Rottingdean — Valley of Rota’s people

- Woodingdean or Woodendean — may be an exception, first appears unnamed as an isolated farm or outfarm, to the south of the modern village, on a 1714 map and may have acquired its name by copying the form of others in the area.

The latest thinking is that these peoples’ names, recorded in the names of their settlements, were not heroic Saxon warriors, conquerors of little corners of England. They were just local leaders, farmers, estate managers — founders of new farm settlements, but worthy of being remembered all the same. Kingston near Lewes was not the residence of royalty, a great chieftain, but merely one of many royal landholdings, bringing in an income to swell their coffers.

An observation of my own (which may or may not be original) relates to their geography. They are (almost) all located:

- In the shelter of a ridge to their south-west, the prevailing wind direction;

- At the coming together of two or more valleys; the exceptions, Falmer and Kingston, had a permanent pond or a spring respectively.

All of these factors would mean that their valley bottom soils would potentially be deeper, have a larger collection area for the run-off of rainfall, and the effects of winter gales would be less — hay ricks would be less likely to blow away (a problem reported by Guy Woodman the farmer at Balsdean from 1925-1942).

The locations of settlements at the meeting point of two (or more) valleys would have served a further purpose. Their arrangement is like that of a capital ‘Y’, consisting of two upper branches and one lower, with the farmstead in the middle. This enables the classic Medieval three field system – one in each of their fertile bottoms – a system possibly developed in the 8th century.

Norman Downs

The history of Kingston near Lewes from the Norman times to the present has been well documented by writers such as Joseph Cooper(4), Mrs Alexander(5), Roger Taylor(6), Margaret Thorburn(7) and Charles Cooper(8). It has been summarised in Lewes District Council’s Kingston Conservation Area; Character Appraisal of April 2007, which is available on the Internet. As far as the character of the Downs was concerned, the rabbits that they brought with them ended up being one of their major legacies. To the south-west of Newmarket Hill is Warren Hill, between the present-day Brighton Racecourse and the villages of Ovingdean and Woodingdean. There is evidence that this was the site of a medieval warren, an enclosure for the breeding of rabbits. There is a thirteenth century document complaining of the damage caused by the rabbits that had escaped.

The Norman Conquest brought new landlords, but our Downland peasants remained the same; sowing and reaping, baking and brewing, shepherding and milking. One new landlord, in about 1130, was the Lewes Cluniac Priory, whose prior was brought over from France by William de Warren, who fought with William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. He gave them land, churches, mills and other industries, along with the people who looked after them, all from his holdings in thirteen counties, so they could pray for his and his family’s souls in perpetuity. Others made more modest donations. Lewes Priory’s Chartulary included many of those places mentioned in this book:

- Balmer; (1091–1098) William de Warren gave 2 hides [the amount of land sufficient to support 2 (extended?) households]; and a hide of land which Eustace held and which belonged to the manor of Falmer; Godo also gave 2 hides;

- Balsdean; (1091–1098) Hugh son of Hugh gave a hide; (1095) William de Warren gave the chapel; (c. 1175) Earl Hamelin de Warenna gave 100s. of land in Balsdean, namely 2½ hides and 1 virgate of land [a quarter of a hide] for the welfare of my soul and of Countess Isabel my wife and our children and for the souls of our ancestors, in free alms. Wherefore I will and firmly command that the monks have and hold the said alms well quietly freely and honourably as free and perpetual alms. And I and my heirs will acquit these lands at our own cost towards the King and towards all men from all customs and services. And the monks after our death shall celebrate the anniversaries of Countess Isabel my wife and myself;

- Brighton; (1091–1098) Wiard gave half a hide and the tithe of his demesne [the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor for his own use]; (c. 1095) Ralph de Kayneto gave the church and the tithe [a 10% tax on all things for the church] which he had in that vill [land in a parish or manor]; William de Warrena gave two churches [!!] and in the same vill half a hide of land; (c. 1147) John de Kaysneto gave to God and St. Pancras and the monks half his land of Bristelmeston [Brighton] which his father had on the day when he was alive and dead, with all the men belonging to the land and with pasture and its other appurtenances; (c. 1090) William de Warrena also gave the tithe of my hay and half a hide of land at Bristelmestona which was Wiard’s, and Brithmer de Bineham with the land which he held of Ralph son of Warin; (c. 1175) William de Garenna gave 2 virgates of land and the third part of a quarter of a virgate of land with all its appurtenances in the vill of Brittelmeston, which lands Ailwin the skinner (peletarius) and Aluric Asse hold. These men I have given to the said monks with the said land and with their wives and children in exchange for the mill of Mechinges [Meechings, Newhaven] which my father gave them in alms when he himself became a monk at Lewes;

- Falmer; (c. 1089) William de Warrena gave to them the underwritten manor of Falemera by name whatever [he] had in demesne there; (1091–1098) and in Crandona [Crandean, Falmer] the land which Hudelin [or Hugelin] held; (c. 1095) and the land which the burgesses of Lewes held in Crandona; and the land which Wlwin son of Golle used to hold there; (c. 1150) and two hides of land in Falemela which William de Sancto Pancratio held; and in the same Falemera two hides of land which belonged to Plumpton; a hide of land at Falemera all of which Fredesend daughter of Hugh son of Rainer gave for the soul of her father;

- Iford; (c. 1100) William de Warrena gave the church of Iforda with its appurtenances, and the marl-pit which is at the end of [their] vill, with the land which is there round the marl-pit, and the meadow which belongs to the same land; (1091–1098) the church of Yford which Hugh son of Golde gave them [Iford almost certainly had only one church, so Hugh gave the church but William may have ‘owned’ Hugh]; And the tithe of Hugh son of Golde; (? c. 1145) William de Warrena also gave to the same monks in the same freedom two hides in Yfordia which Guy (Wido) de Menchecurt held, to hold in free alms until the said land may be freed from all claims and the monks may possess it quietly and peaceably for ever; also two hides of land in Yfordia which William son of Godwin holds and [William de Warrena] gave to them William himself with his children, so that William himself may hold from them one of those hides for 30s. so long as he pays them properly, but the other hide they may have in demesne as their own;

- Kingston; (1091–1098) Warin the Sheriff gave a garden in the vineyard, and all his tithe of Kyngestona; Hugh son of Golde gave in Kyngeston the tithe of two hides; And a hide and a half of land which Ailwin de Wincestria held in Kyngestona; (c. 1095) And William de Warrena willed the church of Kyngestona with one acre of land (which Peter the Sheriff gave there for the making of the church) on which the church stands with its appurtenances and in the same will 8 hides of land; (c. 1138) And three hides of land; (c. 1090) And half a hide of land and the gift which Richard de Essarz made to the monks, namely, a hide of land in the same Kyngestona in free alms.

- Ovingdean; (c. 1095) William de Warrena gave an Ouingedena a hide of land; (?) Jordan de Blosseuilla gifted the land of Ouyngedena; (c. 1170) Isabel Countess de Warenn’ with the goodwill and consent of her lord Hamelin Earl de Warenn’ grant and confirm the gift which her said lord has made to God and St. Pancras and the monks of 24 hides of land in Ouingedene;

- Rodmell; (1091–1098) William de Warrena gave the tithe of all things at Redmelde; (c. 1095) And the church of Radmelde;

- Rottingdean; (1091–1098) William de Warrena gave the church of Rottingedena; And the tithe of the land which he had in Rottingedene; And a hide of land which William de Petroponte gave in Rottinged; (c. 1095) And in the same Rottingedena a hide of land and a messuage beside the cemetery; (1147) half my land of Rottingedena, with men and pasture and all other appurtenances of that land free quit and discharged of all things, as it was divided in the year in which I went to Jerusalem; And Rainald de Warenn’ allowed that hide of land to be given to God and St. Pancras and to him which Ralph de Angieus has given him of his land in Rottingdena;

- Swanborough; (c. 1089) William de Warenna gave in perpetuity the underwritten manor of Swambergha (c. 1090, 1095 & 1331, Swamberga, the land which Bristelm had, with all the liberties privileges and appurtenances whatsoever); (1091–1098) And in Swamberga 5½ hides; Tusard gave them two hides;

Medieval Brighton

The above (slightly edited) document extracts were included in some detail because it provides a fascinating insight into the area and people of that time. Of importance to this history are the first signs of the rise of Brighton — a strong influence on the later history of the Balsdean and Kingston Downs. In the Domesday Book of 1086 Brighton was a village of fishermen and farmers, with the former being the most important. Based on its evidence, Brighton may have had a population of about 400, which is more than double the size of 19th century Kingston. The Priory’s foundation document, just 9 years later, recorded it as having two churches — a small village would only have one — it is better described as a small town, or at least on its way to becoming one. By 1312 it had been granted a weekly market and an annual fair. Brighton’s earliest map, of 1514, shows it to be a small town formally laid out in a grid pattern, strongly suggesting that its fishing industry was sufficiently important for money to be invested in the town’s layout, sometime between the late 13th and 15th centuries.

All of this has been strongly influenced by Brighton’s geography. It is in the centre of a wide bay between Selsey Bill and Beachy Head, where the coastal plain to the west, meets the chalk cliffs to the east. It is also midway between two important Sussex rivers, the Adur and the Ouse. Both are tidal beyond the points where they cut through the north scarp of the South Downs, and provided strongly defensible harbours inland of the coast. Both are guarded by Norman Castles, and formed important administrative centres. Lewes, the county town of Sussex, was the chosen base of the Barony of William de Warrene, who owned all three of the manors which held land in Brighton. Brighton’s main manor, which was responsible for Brighton’s fisherfolk, was a joint manor with Lewes. Easy access to networks of trackways across the well-drained South Downs linked transport by sea and land.

Tidal currents of the English Channel, as was mentioned earlier, create a phenomenon known as longshore drift. It causes flint pebble beaches to move eastwards, blocking the mouths of rivers and forcing them to exit further east. Thus the action of the sea helped create ancient harbours at Portslade (Aldrington) and Seaford, whose entrances were a considerable distance away from their modern day equivalents at Shoreham and Newhaven respectively. Such secure, protected, river based harbours were largely used for the transport and trade of high value goods, and since the Adur and the Ouse were tidal past their crossings of the Downs, the affluent inland towns of Steyning and Lewes built castles to protect their inland ports, enabling merchants to become rich enough to build fancy houses and make names for themselves.

Meanwhile the wide shingle bar south of Shoreham extended many miles eastwards, as far as Brighton’s Poole Valley. Created by the actions of the Adur and the sea, part of it survives today under Hove Lawns. This extensive beach provided the location of Brighton’s missing street. The 1514 map shows North Street, with West Street, Middle Street and East Street ending at the edge of a low cliff. But down on the beach itself was the former location of South Street, where many of the town’s fishermen lived. A series of storms in the late 17th century and the Great Storm of 1703 caused its demise (of which more later).

Apart from the escape of King Charles II, until it became a fashionable seaside resort, it possessed no nationally important persons or buildings. But the fancy buildings and people of Shoreham and Steyning depended on riverside docks that were expensive to maintain; requiring dredging and repairs. But Shoreham’s flint pebble nuisance was both Medieval Brighton’s greatest asset and its eventual downfall, as we will discover.

Smuggling

Because this downland hill was both central and yet remote from habitation it would have seen more than just shepherds and travellers on legitimate business. By the eighteenth century, to avoid paying high taxes on certain goods, many people from the area turned to smuggling. The village of Rottingdean, on the coast to the south, was especially famous for its smugglers. They were romanticised in ‘A Smugglers’ Song’ by Rudyard Kipling, but the realities were very different. They were organised gangs best compared with the South American drug smuggling cartels of the present day. In one instance, as many as two hundred men were recorded unloading smuggled goods from a boat in Cuckmere Haven in broad daylight. Anyone trying to stop their activities, whether local farmer, parson, excise man, or judge, would be likely to have either their property or persons damaged, and killings were not unusual, for the profits to be made were considerable.

On the 2 inch to the mile Yeakell and Gardner map of Sussex, which was begun to be surveyed in about 1770 and published between 1778 and 1783, there is a curious symbol on the summit of Newmarket Hill that looks like it represents a gibbet. These were iron cages in which the dead body of a notorious criminal were placed. They were usually in a public yet remote roadside location, as a deterrent to criminals. As we later discovered in our researches, the Downs surrounding Newmarket Hill very much had a reputation for disreputable characters. However, this is highly unlikely because gibbets were famous tourist attractions and therefore well known.

More likely, despite a lack of proof, is that it was a signalling station. The symbol is of a vertical post topped by a diagonal bar, such as might have supported a fire cage – known to have been used elsewhere for signalling purposes in times of war. It was the Duke of Richmond who commissioned their mapping work. He was responsible for the defence of Sussex and had been encouraging the British Government to invest in detailed mapping for military purposes. The influential Pelham family in nearby Stanmer House were unable to see any of the surrounding hilltop beacons in published lists. It does have an excellent view of Newmarket Hill, from which many former beacons can clearly be seen. Was this something personal to the Pelham family? During the second half of the eighteenth century military tensions were rising, reaching full blown war status during the Anglo-French War of 1778-1783 (the same dates as the publication of the Duke of Richmond’s ‘Yeakell and Gardner‘ map of the coast of Sussex). The coast of Sussex was on full invasion alert and local militias were organised.

I have means, motive and opportunity that this strange symbol could be a defensive signalling structure. Preliminary research by Peggy and I failed to find anybody who has investigated this symbol – there are extensive archives and it is interesting period of history to research. Sadly we don’t have the time to research it further ourselves.

Shepherd scholar

There was a short period of peace before the start of yet another war with France in 1803. During that peace, the young shepherd John Dudeney (pronounced like the word scrutiny), whilst tending the Kingston flock on Newmarket Hill, managed to find the peace and quiet necessary to studying the books that enabled him to give himself an education.

He was born in Rottingdean in 1782, and started tending the Rottingdean flock at 8 years old. He was encouraged in his studies by the Rottingdean vicar, Dr. Hooker, who most interestingly was very much involved in smuggling (of whom more later). John Dudeney moved to Kingston when he was 17 years old and, with 9 years of experience, was now responsible for taking all of Kingston’s 1,400 sheep up onto the Downs every day. This was midsummer, 1799, and he stayed there 3 years. Kingston’s old shepherd was, at this time, too infirm to manage the steep climb up above the village to Newmarket Hill. It may be that his new boss was also involved in smuggling, based on reminiscences recorded by Mrs Alexander in her book on Kingston.(9) Whilst there is no evidence that John Dudeney was ever involved in smuggling himself, he would certainly have known to look the other way in order to stay out of trouble.

At this time the only water on the Kingston downland shown on Yeakell and Gardener’s detailed map was the dew pond on Newmarket Hill, opposite the later location of Newmarket Farm. It was close by that John Dudeney dug a hole in the chalk for his books (his library) which he covered with a large stone. He bought his books and writing materials with his surplus income, largely obtained from catching moles and wheatears. He was thus able to teach himself astronomy, French, Latin, Hebrew, mathematics, and European history. After about 16 years of shepherding he had sufficient education to gain the position of schoolmaster in Lewes, and later owned his own school. He died in May 1852, having advanced himself in a manner that few others attained.

Most of his fellow shepherds and other agricultural labourers would have been illiterate. The next evidence of an ability to read and write was that of Martin Brown, a lodger of Newmarket Farm, in 1868. The first ‘scholar’ of which we are aware in Kingston near Lewes was the 9 year old Elizabeth Timms who in 1871 went to one of the new schools of either Falmer or Kingston, for by then education had become compulsory for children.

[To be added is information about late Georgian Rottingdean and Balsdean].

(1) Bangs, David (2004) Whitehawk Hill; Where Surf Meets Turf. (2) Brandon, Peter (1998) The South Downs, chapter 3, Phillimore and Co. Ltd. (3) Shields, Glen. (2005) The Roman roads of the Portslade/ Aldrington area in relation to a possible Roman port at Copperas Gap, Sussex Archaeological Collections, 143, 135–149. (4) Cooper, Joseph (1871) History of Swanborough Manor. (5) Mrs Alexander (1950’s), edited and reprinted by Hazel and Arthur Craven, Record Book of Kingston. (6) Taylor, Roger (1990) A History of Kingston-near-Lewes. (7) Thorburn, Margaret (2001) An Account of the Manor of Hyde: Kingston near Lewes, Sussex. (8) Cooper, Charles (2006) A village in Sussex: the history of Kingston-near-Lewes. (9) An unnamed late 18th or early 19th Tuppen, was a shepherd.

Previous: Chapter 1. Introduction