A struggle to make it out of my tent in time for *the* bus. My initial destination was brunch in Niwbwrch (Newbury).

After a delicious club sandwich, reviving coffee and an excellent set of instructions on how to get to my my destination I was off!

The beautiful forest was planted on top of a sand-dune. The grains of sand – a form of oxidized silicon – is relatively inert and hard. Therefore, thousands of years ago, when glaciers scoured the rocks between here, Northern Ireland and Scotland, the commonest surviving remnant of the crushed rocks was wind blown and water washed sand.

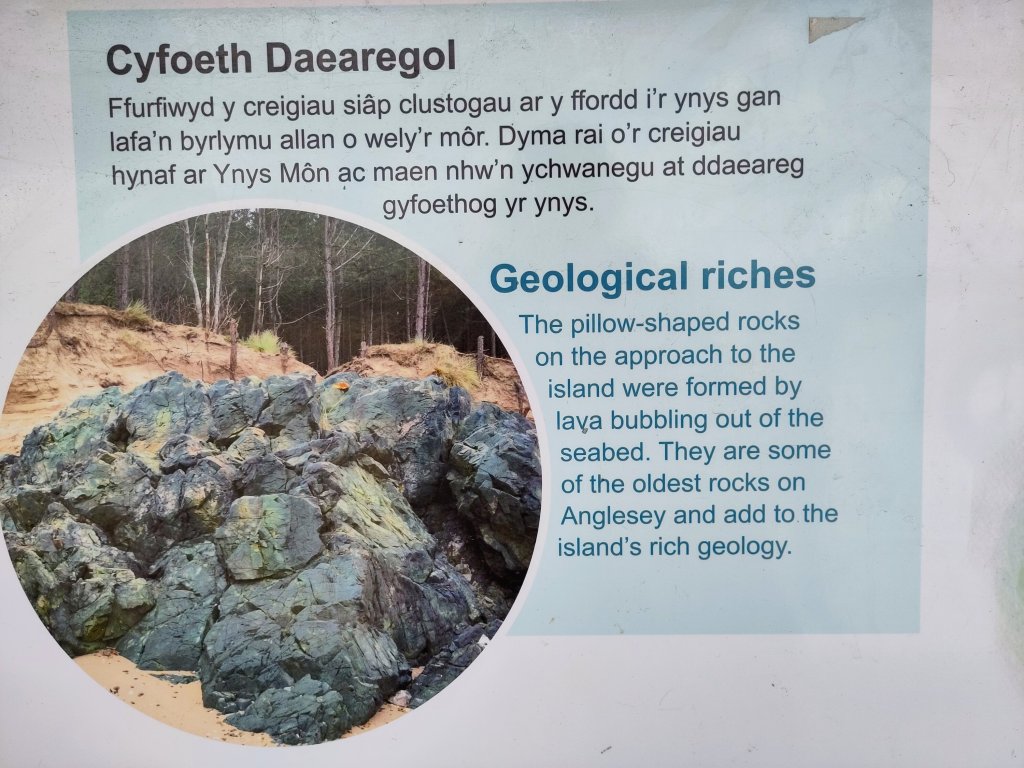

Pillow Lava

My first rocks were exactly what I hoped to find – great billows of solidified pillow lava. Easy to recognise 🙂 Proof of volcanic seabed activity, hundreds of millions of years ago.

The outermost of the red-hot lava-flows, when they hit the cold seawater, they exploded into tiny fragments. The parent lava rock – basalt – is a dark green-ish colour. But the exploded ashy material has oxidized to a rusty red. The yellow colour on top is a lovely crusty little lichen that, more than half a billion years after the lava was first extruded out of the Earth, found itself a home on the edge of this sandy beach.

How do I know that this lava is about 580 million years old? I could say that I read it in a book. But the authors read it in a scientific journal – probably published by the recent Japanese team of geologists who made an in depth study of Anglesey’s geology.

Japan is a series of volcanically active islands on the edge of the Pacific Ocean’s ring of fire. Some of Anglesey’s ancient geology has been observed as happening in present day Japan, such as the recent terrible earthquake which triggered an extremely destructive tsunami (tidal wave).

The hole above – and I saw a few of them on my geological travels – was made by a rock coring drill, by scientists needing to take samples back to their laboratory for dating.

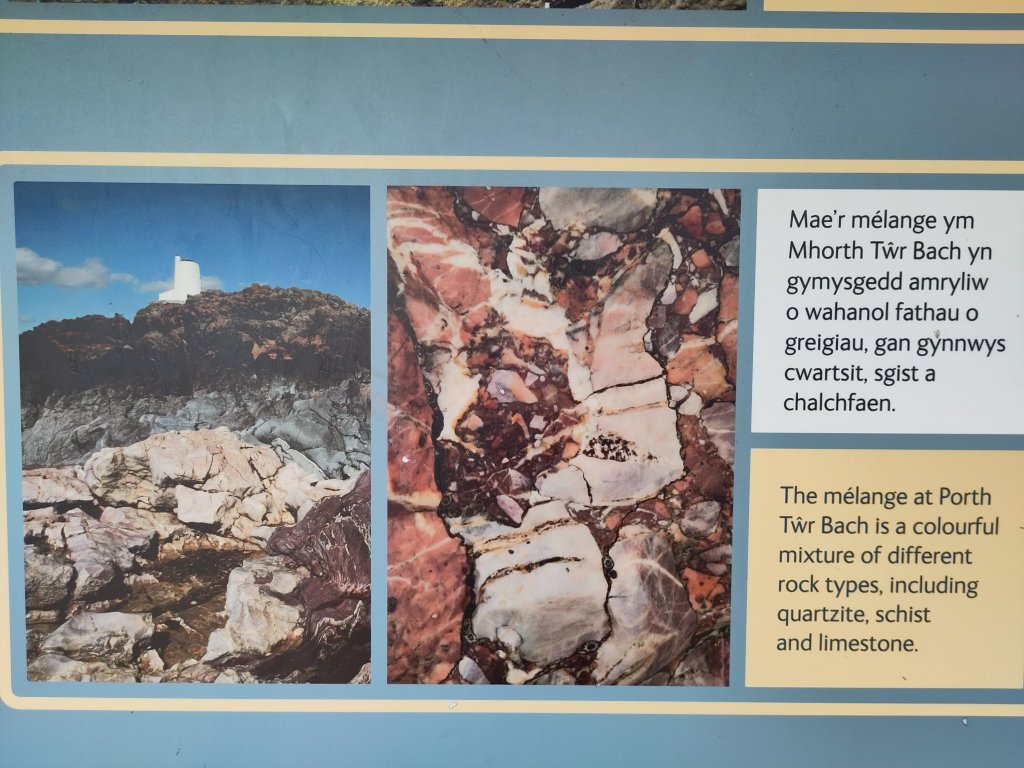

Mélange

I love the word mélange. A random blend or mixture of rocks all stuck together like fruit and nuts in a Christmas Pudding 🙂

The GeoMôn geological glossary gives the following definitions (with commentary from myself):

- Breccia: a rock consisting of more than 30% poorly sorted, angular fragments (clasts) greater than 2mm in size (cf. conglomerate).

- The angular nature of the inclusions indicates their being associated with a sudden catastrophic event such as a landslide, flash flood or tsunami.

- Conglomerate: a sedimentary deposit containing more than 30% of rounded rock fragments (clasts) larger than 2mm in diameter (cf. breccia).

- Often called pudding stone, with its inclusions having been rounded by the action of continuously moving water, such as a river or waves on a beach.

- Mélange: a large body of rock comprising chaotically arranged rock fragments of varied sizes contained within a fine-grained matrix. It is formed from sediments and rocks on the oceanic crust that are underplated at a destructive plate margin (Llanddwyn and Cemaes Bay).

- Mélange is therefore (if I’m right) a kind of breccia.

Destructive Plate Margins

Do you remember what I wrote in Ancient Geology 4.1: Wandering (In)Continents? How the blueschist rock under the Marquess of Anglesey’s Column was pillow lava that erupted from the centre of an ocean which then found itself on a sideways moving ‘conveyor belt’ as continual eruptions of new lava pushed the old lava sideways till it had nowhere to go – when it met a continental plate – except downwards.

Why downwards? Basalt – what oceanic crust is mostly made of – is heavier than most continental rocks – whose parent is largely made of granite, which is less dense. Imagine oil floating on water. The oceanic crust is heavier than the continental crust, so it sinks downwards, back towards the centre of the Earth. This is called subduction. It happens at a destructive plate margin.

[Edit: I now know that the reality is a little more complex – but I think that what I wrote is close enough not to need rewriting.]

Mélange Constituents

Jasper

The ocean floor is covered in all sorts of other stuff. When it is near dry land, fine grains of sand can be eroded by ice; and the wind can blow them out to sea, and rain can form rivers which can also wash sand out to sea.

There is often iron present in sand – which gives it a nice orange colour. However, when sand meets very, very hot lava it can vitrify – turning into a glass like substance called chert or chalcedony. In the presence of iron it can become a beautiful bright red coloured stone.

Other rock fragments include limestone, of which more in part 8 [to be written Tues or Weds 🙂 ].

Accretionary Wedge (or Prism)

I like Wikipedia and I like diagrams. The diagrams in books about Anglesey were somewhat confusing. But I begin to imagine that I understand thanks to Wikipedia 🙂

Ok, the lithosphere is the outermost bit of the Earth which is solid. The top-most part of it shown on the left side of the above diagram is the oceanic crust, heading towards and then below the continental crust, shown on the right. Where they meet, on the ocean side is a trench, but on the continental side of the trench is a wedge of material, called here, the accretionary prism.

The frictional forces at the entrance to the subduction zone cause the layers of the oceanic crust to delaminate. I read (somewhere!), in relation to the formation of blueschist, that the prism contains material arranged like a cascade of regularly falling dominos. The actuality, it seems to me, is that one should imagine all the dominos initially all lying flat, and that friction at the entrance to the subduction zone pushed them upwards.

The accretionary wedge/prism concept explains why it is hard to understand on the ground. It is a geological mess, an absolute Mélange. But a pretty one all the same.

What Next

I deliberately missed out the limestone and marble formations I saw on Llanddwyn – I am saving them for the write up of Tuesday’s outing – which I may not write up till my return journey on Wednesday.

The Blessed Isle

What more can I say…

<- Ancient Geology 5.1: Love and Melange

<- Ancient Geology 6.1: Granite, Serpentine and Mantle Plumes

2 replies on “Ancient Geology 5.2: Llanddwyn, Island of the Blessed”

Enchanted eels! Enchanting.

The Mélange is so richly varied and beautiful.

I’m sure I could fall asleep on that pillow rock, it looks so soft.

[…] Ancient Geology 5.2: Llanddwyn, Island of the Blessed -> […]